My blog

posts — the individual dated entries; there must be about 400 of them — rarely

get more than two or three readers, and it might even be the same reader two or

three times. Just here and there a post might creep into double figures. The

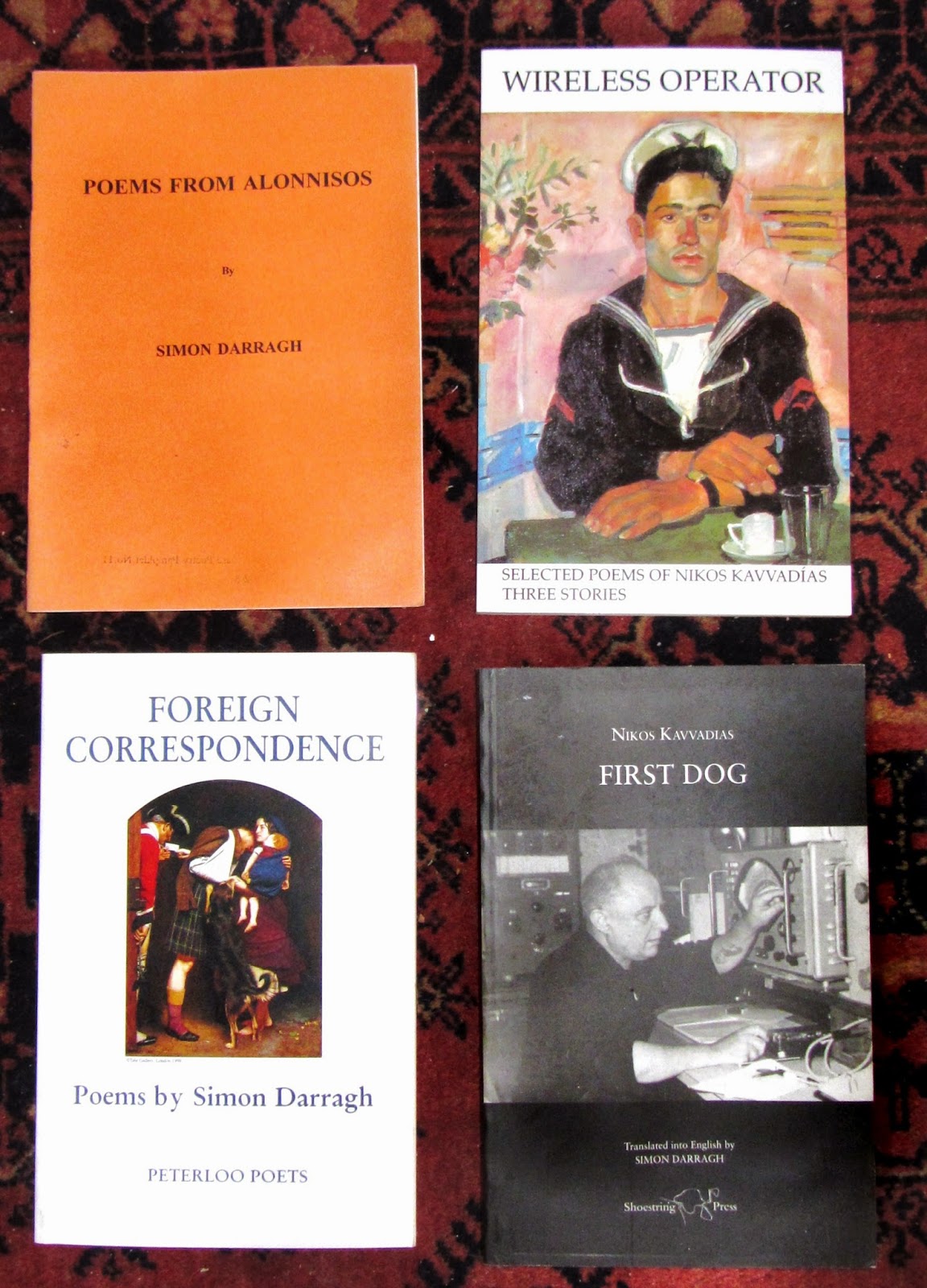

exception is a post called ‘Wireless Operator’, which is the title of my book

of translations of the poetry of Nikos Kavvadias. That post, which consisted

simply of one scanned page from the book, has had to date 272 readers. Probably

there is a link to it from some other site. It suggests there is an interest in

the work of Kavvadias among anglophone readers, so here’s my translation of

another of his poems:

Marabou

Nikos Kavvadias.

The sailors who I live with say

I’m vile, thick-skinned and base,

and never go with women; that

I hate the female race.

I’m vile, thick-skinned and base,

and never go with women; that

I hate the female race.

They say I take hashish and coke,

caught up in some dark passion;

they talk of tattoos head to foot

in deep, obscene incision,

caught up in some dark passion;

they talk of tattoos head to foot

in deep, obscene incision,

And many other filthy horrors —

all made up, all lies:

what cuts me to the quick I never

told, and no-one knows.

all made up, all lies:

what cuts me to the quick I never

told, and no-one knows.

But now, as tropic night falls, and

the Marabou fly west,

I’m moved to set the secret down,

the fixed pain from the past.

the Marabou fly west,

I’m moved to set the secret down,

the fixed pain from the past.

I, novice on a postal ship —

Egypt, Southern France —

she, an alpine flower — we loved

as brother, sister, friends.

Egypt, Southern France —

she, an alpine flower — we loved

as brother, sister, friends.

Slim and sad aristocrat,

a rich Egyptian’s daughter —

he’d killed himself — her sorrow sought

rest on land or water.

a rich Egyptian’s daughter —

he’d killed himself — her sorrow sought

rest on land or water.

She had Bashkirtseff’s Journal* — loved

Avila’s Saint Teresa —

she’d read me sad lines of French verse,

or gaze at the horizon,

Avila’s Saint Teresa —

she’d read me sad lines of French verse,

or gaze at the horizon,

And I, who’d only known whore’s flesh,

my soul dulled by the sea,

would listen with lost infant joy,

a prophet’s ecstasy.

my soul dulled by the sea,

would listen with lost infant joy,

a prophet’s ecstasy.

I clasped a small cross round her neck,

took the purse she gave.

Then — the world’s most sorry man —

the port where she must leave.

took the purse she gave.

Then — the world’s most sorry man —

the port where she must leave.

On freighters I would think of her

as guardian angel, hope;

her picture my oasis in

the desert of the ship.

as guardian angel, hope;

her picture my oasis in

the desert of the ship.

Here I would stop — the hot wind burns

and my hand is shaking —

the tropic flowers stink — far off

a Marabou is croaking.

and my hand is shaking —

the tropic flowers stink — far off

a Marabou is croaking.

Well … one night in some foreign harbour —

whiskies, gins and beers —

I staggered to the lost and stinking

houses of the whores.

whiskies, gins and beers —

I staggered to the lost and stinking

houses of the whores.

Shameless women catch the sailors —

someone playfully

pulled off my cap — an old French trick —

I followed, doubtfully.

someone playfully

pulled off my cap — an old French trick —

I followed, doubtfully.

A small room — dirty like the rest,

paint peeling off the wall —

a human rag, with croaking voice

and dark eyes, straight from hell.

paint peeling off the wall —

a human rag, with croaking voice

and dark eyes, straight from hell.

We came together in the dark;

my fingers felt each bone.

She stank of absinthe. I woke up

“With rosy-fingered dawn.”

my fingers felt each bone.

She stank of absinthe. I woke up

“With rosy-fingered dawn.”

A sorry sight she looked, and damned,

by the light of day —

horror shook me as I took

my wallet out to pay.

by the light of day —

horror shook me as I took

my wallet out to pay.

Twelve francs … she screamed, she stared wild-eyed —

now me, now the purse —

then I noticed, hanging there

round her neck — a cross.

now me, now the purse —

then I noticed, hanging there

round her neck — a cross.

I ran out capless to the street,

wandered, staggering, mad,

the sickness that still tears my flesh

already in my blood.

wandered, staggering, mad,

the sickness that still tears my flesh

already in my blood.

The sailors who I live with say

I’ve let no woman have me

for years; that I sniff coke — but if

they knew all, they’d forgive me.

I’ve let no woman have me

for years; that I sniff coke — but if

they knew all, they’d forgive me.

My hand shakes … fever … lost, I watch

a Marabou on the bank.

My loneliness is like his, as

he stupidly stares back.

a Marabou on the bank.

My loneliness is like his, as

he stupidly stares back.

Translated by Simon Darragh.

If you want more, you could always splash out and buy the book. It’s available from Enitharmon Press.

No comments:

Post a Comment